The 1956 Bay Area Rapid Transit master plan was full of high hopes and soon-to-be-failed dreams: BART cars crossing the Golden Gate Bridge. Whisper-quiet trains arriving every 90 seconds. Stations as far away as Santa Rosa, Napa and Fairfield.

But the part of the plan that sounded most like science fiction actually happened.

“The heart of the rapid transit system recommended for the Bay Area by 1962 is its electric train tube linking downtown San Francisco and downtown Oakland,” The Chronicle reported on Jan. 6, 1956. “The tube beneath the Bay … would avert the necessity for a costly second Bay Bridge.”

With a growing majority of Bay Area residents born after the construction of the BART Transbay Tube, it’s easy to take the engineering marvel for granted. But a trip through The Chronicle archive — which details every victory, setback and tube joint filled with squirming crabs — adds perspective.

They built a transit line. At the bottom of the sea.

Here’s the tale of that miracle of engineering’s planning, construction and debut, as told in archive stories and images:

The 1956 transit planning report gave two options for connecting San Francisco and Oakland: a $5.8 million “minimum plan” that would send BART over the Bay Bridge, and the “optimum plan,” an underground tube costing $73 million.

The Bay Area Rapid Transit Commission that created the report strongly recommended the latter, citing the ease on bridge traffic and the speed of trains in the tube.

“The tube would … permit rapid transit riders to go from San Francisco to Oakland in 11 minutes — less than it now takes to go from Montgomery Street here to the San Francisco Civic Center,” The Chronicle reported. Alternatively, “even modern trains on renovated bridge rails would require 22 minutes to reach Oakland.”

After state construction funds were earmarked, BART in 1961 released an image of the sleek train rocketing through the depths, with a shiny San Francisco skyline in the distance.

The construction details for the transbay tube were revealed to Chronicle readers in 1965, when bidding opened for the project’s four contracts. The 6-mile tube would have 57 segments between 315 and 370 feet in length, built simultaneously from Oakland and San Francisco out into the sea, eventually connecting 130 feet under the Bay just south of Yerba Buena island.

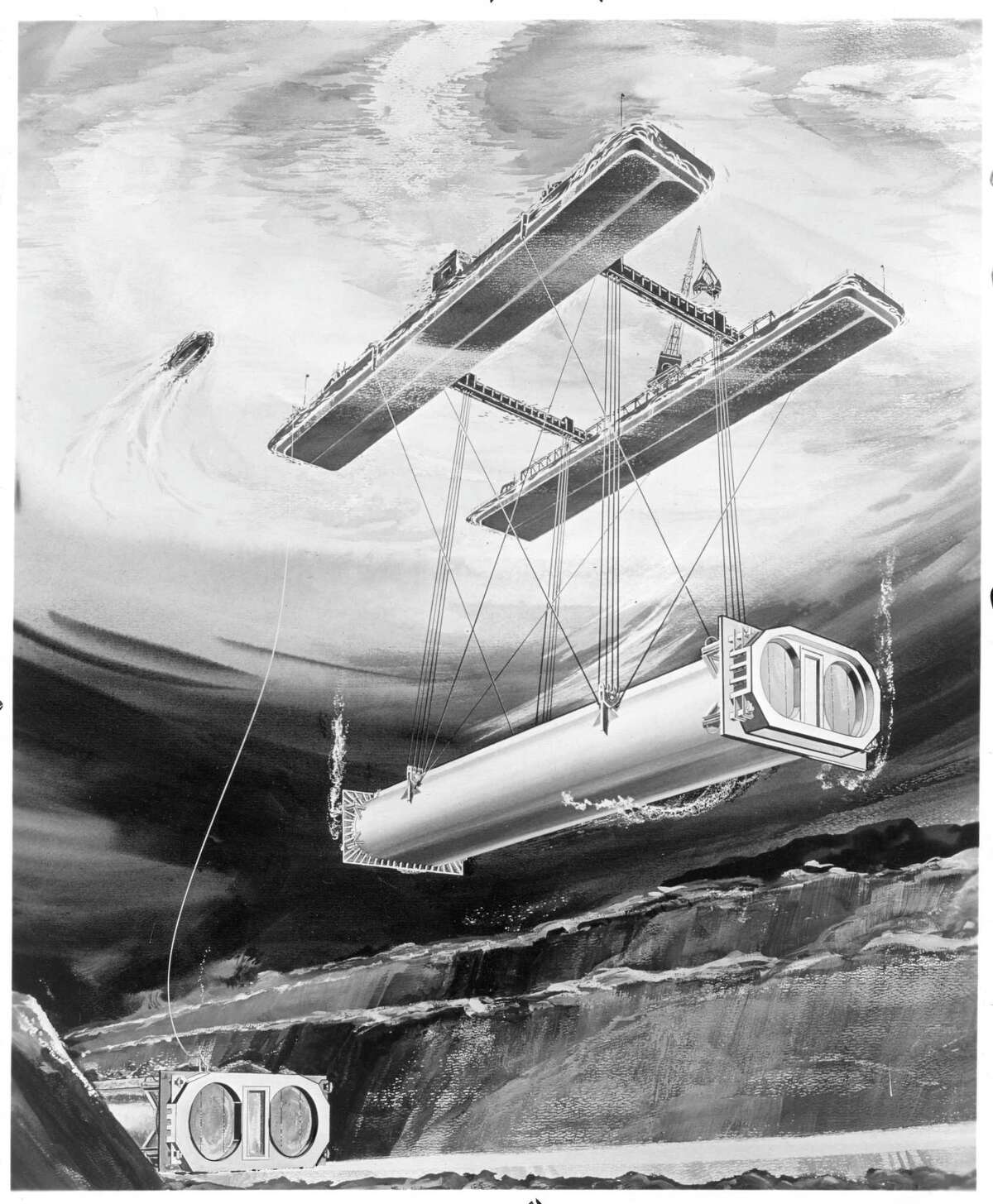

1967: A BART concept drawing shows how the Transbay Tube will be positioned in the San Francisco Bay.

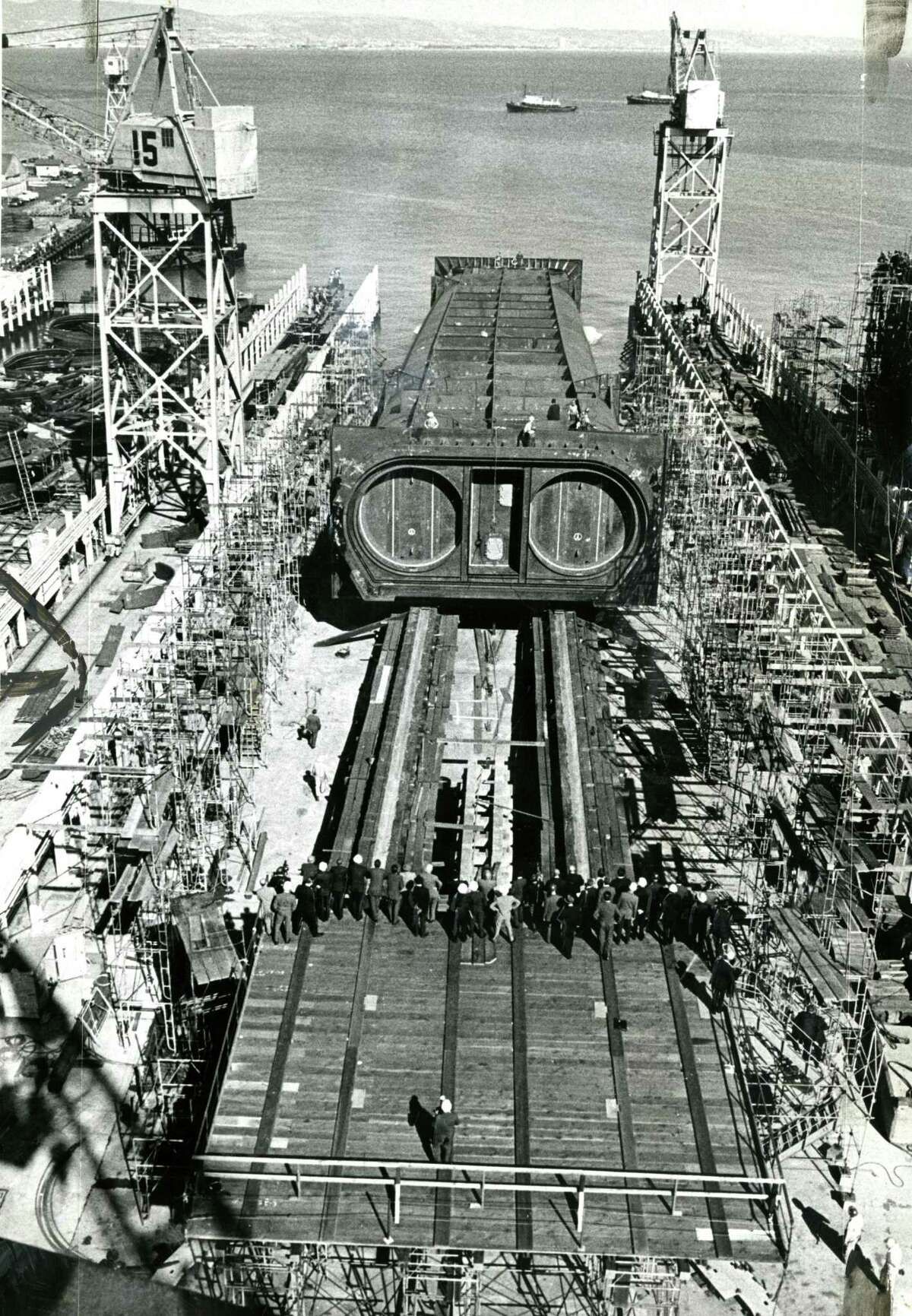

BART 1967The 10,000-ton segments were assembled at the Bethlehem Steel shipyard on the shore near San Francisco’s Dogpatch district, sealed shut on both ends, and towed into the Bay. The tubes were attached to cables, then gravel was piled on top to help them sink to a dredged trench at the bottom of the Bay.

“A catamaran-type placing barge moves the tube sections, one by one, into position, suspended between the big barge’s twin hulls,” The Chronicle reported. “Several barges ‘back-fill’ the trench, piling sand above the gravel-weighted tube sections after they are in place.”

The segments were lowered onto a bed of gravel, where a diver guided the two sides into contact. Hydraulic jacks were used to connect the segments, creating a water-filled gap between the two sealed segment ends that had to be pumped out.

“Men inside the already-placed tunnel open a hatchway after the water is out — and clear from the new joint quite a few trapped fish and crabs, as well as any leftover mud,” The Chronicle reported in 1967.

Sept. 7, 1966: A BART Transbay Tube segment built by Bethlehem Steel in San Francisco slides into the Bay. The transit agency used a 57 segments to build the underwater tube.

Peter Breinig/The Chronicle 1966As the segments were connected, the walk into work got longer. Tube inspector Don Hughes, a popular media figure during the build, watched his commute increase with each segment until he was traveling several miles a day. Workers at the end of the segments deep underwater were called the “Mile and a Half Club,” after the promised electric carts to transport workers were replaced by just three bicycles.

“Electric carts?” Hughes said, partway through the build. “Man, we have trouble getting pencils.”

There were delays throughout the build, including a Bethlehem Steel strike in 1968. Finally, with great celebration, the last tube made its way into the bay on April 3, 1969.

“The 57th and last section of the world’s longest underwater transit tube was lowered into place in a swirl of muddy water in mid-bay yesterday,” The Chronicle reported. “State Transportation Director Gordon C. Luce and BART President Arnold C. Anderson planted a ceremonial ‘No. 57’ flag atop the final section before Anderson fired a signal flare to begin the lowering.”

Workers at the Bethlehem Shipyard secretly placed a table with two chairs, champagne and a note of congratulations inside the sealed 57th segment, as a surprise when the seal was broken by construction crews.

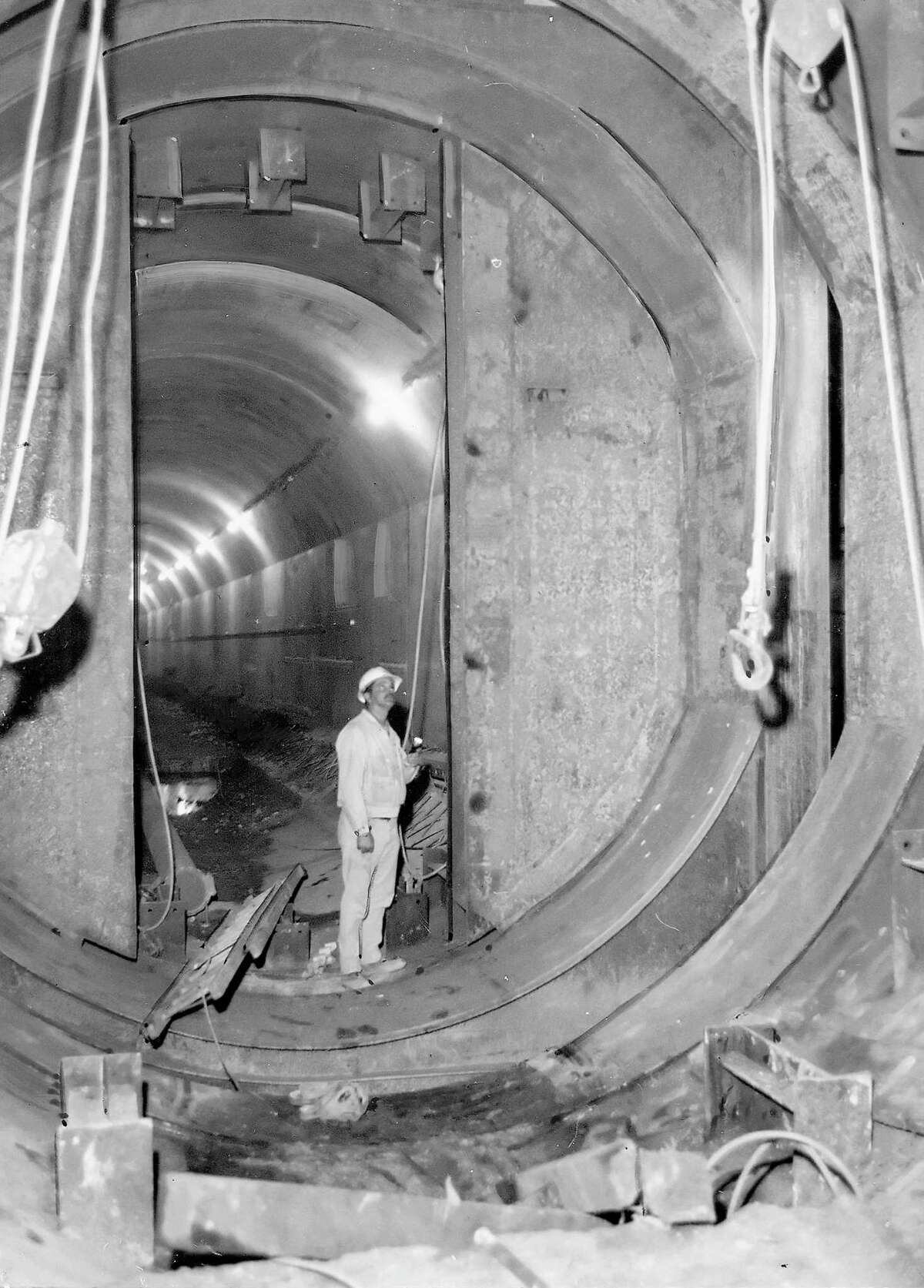

April 23, 1969: BART tunnel supervisor Bill Orr pokes his head through a hole in a wall that was separating the Market Street subway and Transbay Tube.

Art Frisch/The Chronicle 1969The joints were welded, concrete collars were poured and allowed to harden for a week or two, and after a few setbacks involving the last two connected segments, the tube was opened.

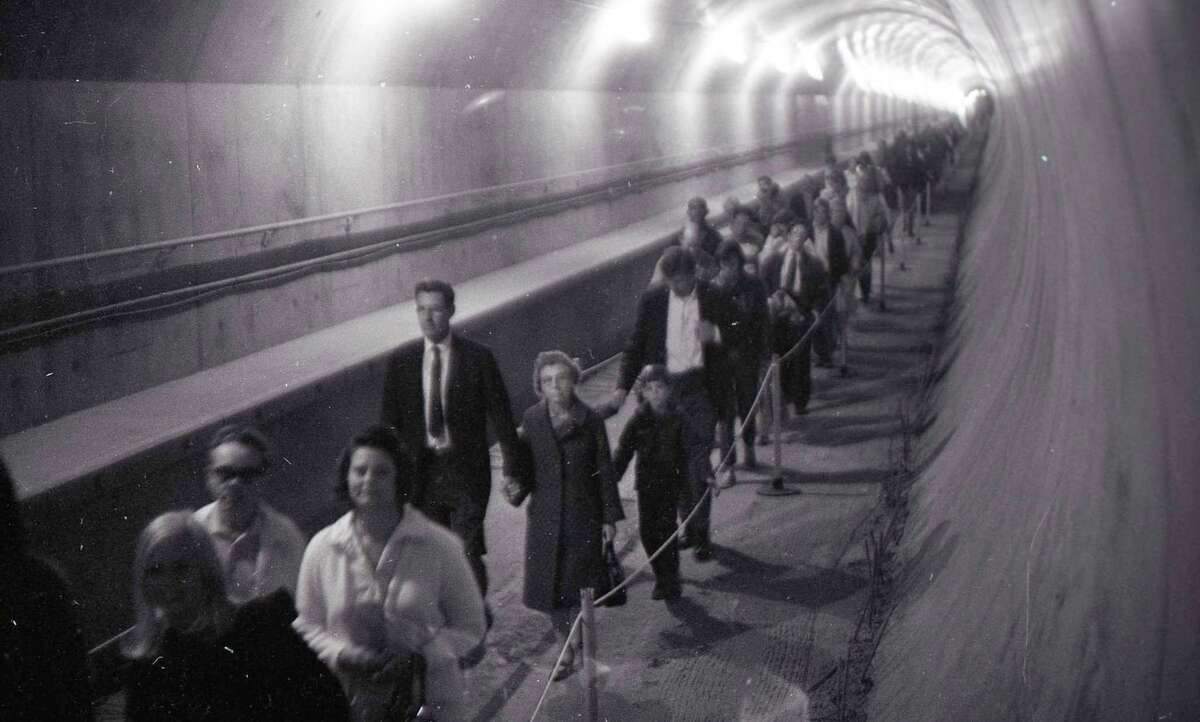

BART tube inspector Hughes was the first to walk the length of the Transbay Tube, but it was nearly a photo finish. When he was two-thirds of the way through the tunnel, heading from San Francisco to Oakland, he ran across several workers coming from the other direction.

A United Press International report described an eerie scene deep under the bay inside the construction feat.

“The air in the tube smells of fresh cement and feels chilly and damp,” the report said. “Dust kicked up by the workmen remains suspended in the light from the seemingly endless string of bulbs along the ceiling of the tunnel.”

Laying down the 57 tubes had taken 17 months and cost $90 million — half of the $180 million total for the transbay project.

May 5, 1969: A table, chairs and campagne were sealed in the last BART Transbay Tube segment, to be discovered by underwater crews when they connected the segment and broke through the seal that would complete the tube.

Chronicle archives 1969San Francisco Mayor Joseph Alioto and Oakland Mayor John Reading held a ceremony at the midway point on Sept. 19, 1969. With no BART cars in operation to take them, Alioto’s group traveled on an elephant-themed train borrowed from the San Francisco Zoo.

“The mayors of San Francisco and Oakland had an underground rendezvous yesterday beneath the middle of the Bay, to dedicate the Bay Area Rapid Transit District’s transbay tube,” The Chronicle reported the next day. “They met 83 feet below sea level, 9,779 feet from San Francisco and 9,334 feet from Oakland, with not a single dribble of water leaking in to embarrass them.”

It was an awkward meeting. An earlier group of rogue dignitaries, led by state Assembly Member Milton Marks, had crossed the tunnel by bicycle a week earlier. (Then-governor Ronald Reagan was invited on the ride, but politely declined.)

And the tube wouldn’t open for passenger service for another five years, as all the wiring and ventilation was completed, the real BART cars arrived and testing commenced. Politicians and transit fans gathered in Oakland to ride the first BART train through the tube on Sept. 14, 1974 … and it promptly broke down with a locked wheel before a single passenger boarded.

But for at least that moment in 1969, near an elephant train at the bottom of the bay, every transit dream in the world seemed possible.

May 14, 1967: A view from inside of the first Transbay Tube segment laid down in Oakland. The stairway in the distance is the end of the tube, and leads up to the surface.

Duke Downey/The ChronicleRemember that 11-minute estimate between Oakland and San Francisco? It turns out the trains could do it in eight.

Peter Hartlaub (he/him) is The San Francisco Chronicle’s culture critic. Email: [email protected] Twitter: @PeterHartlaub